DOL: I’m not aware of any other Black women colorists working in the industry. I may be wrong, but you inhabit this really interesting space. Can you talk about how you maneuver?

KL: I’ve learned to be expansive with the ways I trace my lineage in this space. For example, I look at the work of Black women in a wide range of technical spaces to collage a blueprint for me to follow. Key folks that come to mind include Mary Baptist, who was a projectionist in the 1940s. There’s also Mary Jackson, Katherine Johnson, and Dorothy Vaughn. They were computers for NASA.

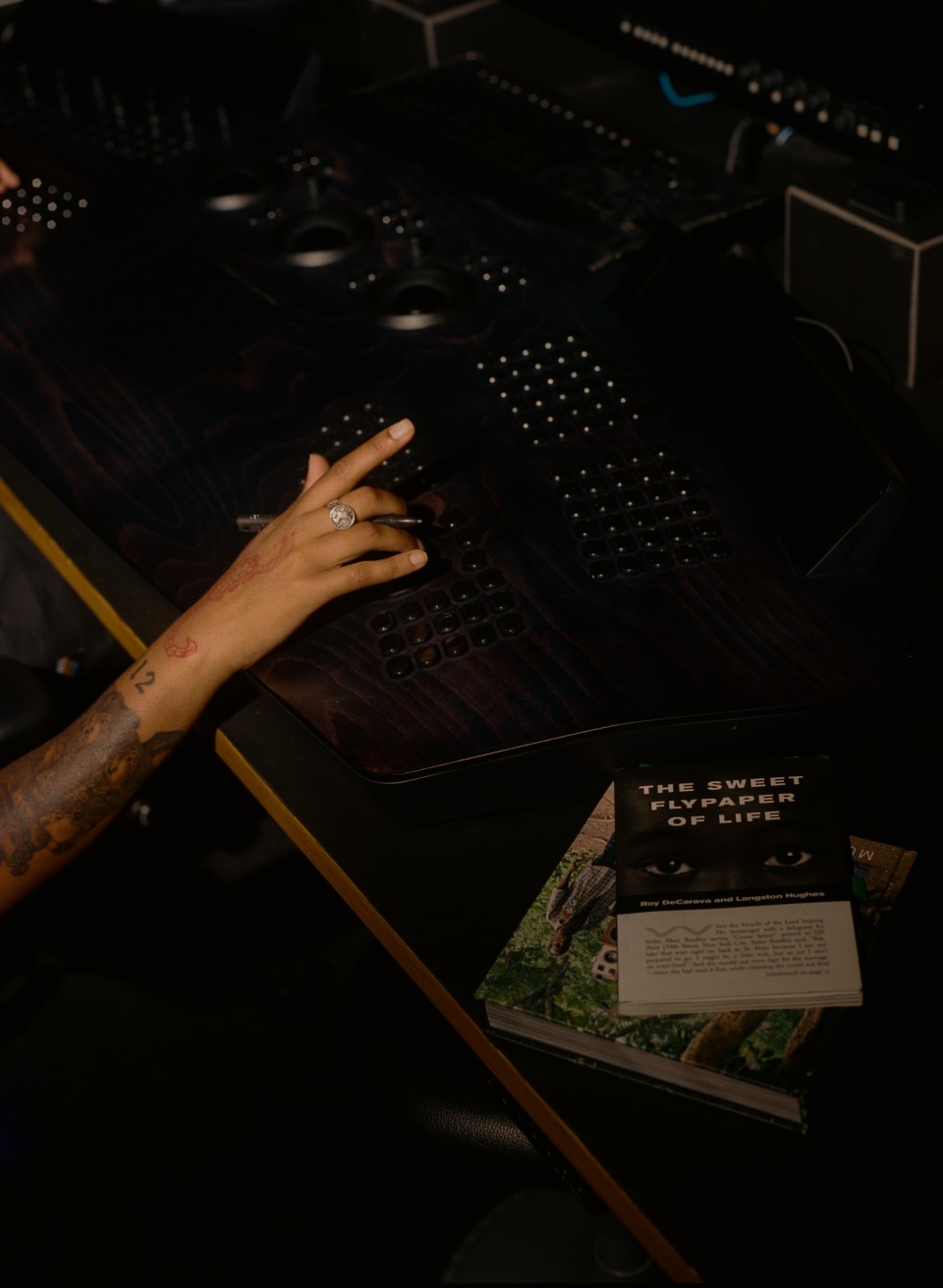

The majority of my time is spent working with color science behind a computer and control board. I’m not the first nor the last to occupy this kind of proximity to this technology. But lately I’ve been really excited about connecting with Beverly Wood. She was a film chemist that worked at Kodak, Deluxe, and Efilm in the ’80s, ’90s, and 2000s. Her chemistry helped author the looks in films like Se7en [1995], Kill Bill 1 [2003] and 2 [2004], and so many others. She’s retired now and is working on restoring a theater in her hometown of Chase City, Virginia. Talking with her and reflecting on the massive scope of her commitment to this medium is my precedent.

DOL: The film industry is a male-dominated space, and I imagine the colorist section aligns with cinema’s hetero-patriarchal, white supremacist lineage. How do you navigate this space? What practices have enabled you to outmaneuver the many challenges that you’ve faced?

KL: To be honest, I am learning how to navigate this space on the fly. I’m constantly rerouting and recalibrating. But sometimes the signal gets lost and I don’t know what I’m doing. That’s when I know it’s time to rest and refresh until I can get a signal again.

I confront the technical challenges by slowing down and tracing my steps. Sometimes the answer to something is hidden by the way you approached the grade. And if I still can’t find the answer, I call my color scientist or the people that designed my software, Baselight.

But then there are other challenges that I can’t solve in the same way I do the technical ones. And these are challenges that are built into the system, and there aren’t enough diversity statements in the world to clean up the problems. Color is one of the most capitalist sectors of post-production. It’s important to think about the legacies of certain companies and how they function internally. They think they are radicals because they color Black narratives, but it’s all an illusion. You’d be shocked at what you see when you break past the surface of their work. I recognize these issues for what they are, but it’s really just a bunch of white noise. I know what my work here is and I am focused and giving it the best that I got. It also helps to have Coloured Only continue as a research practice—so when I’m not color timing, I’m sourcing and surveying images that support the calibration of my eye.