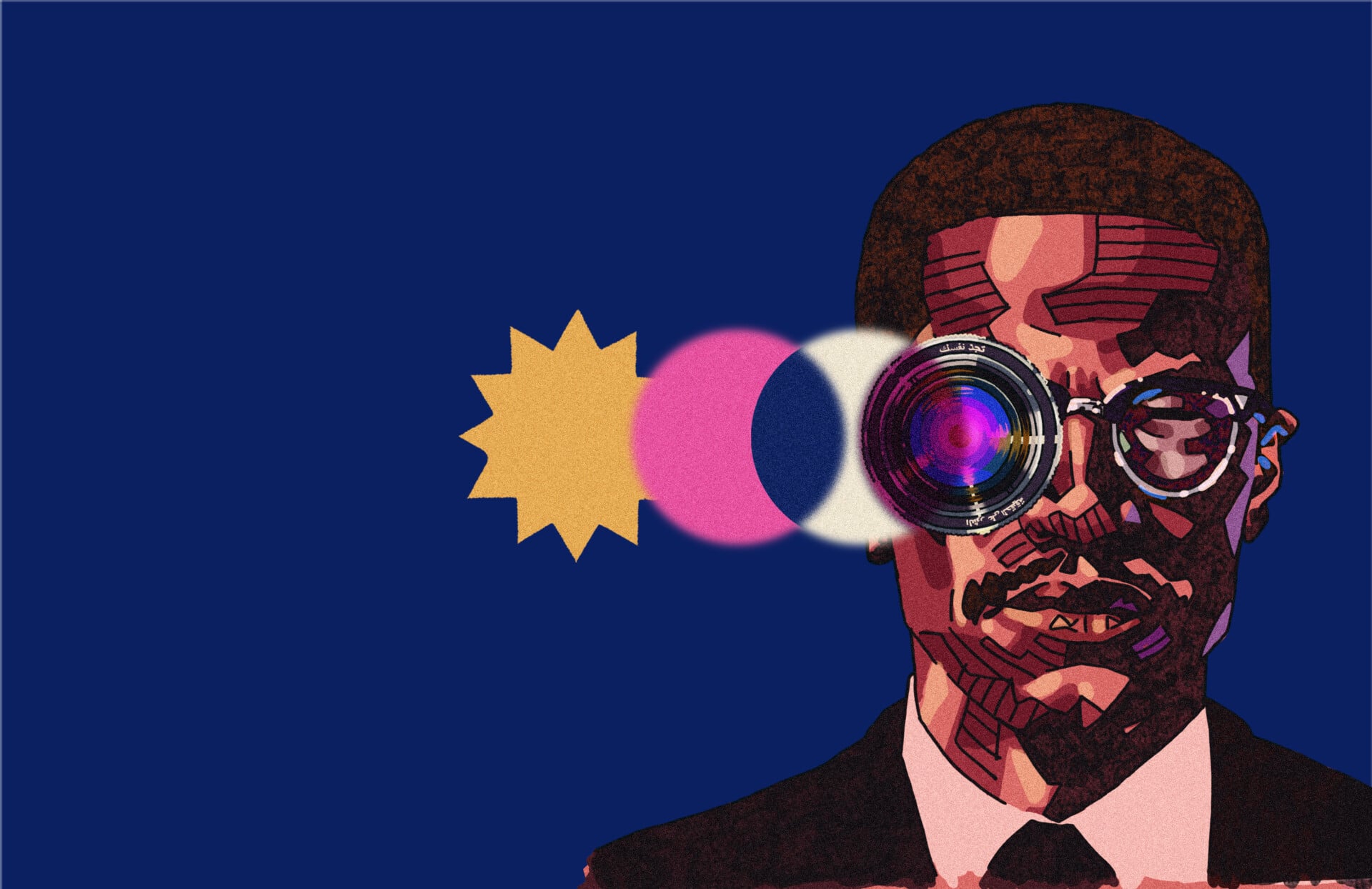

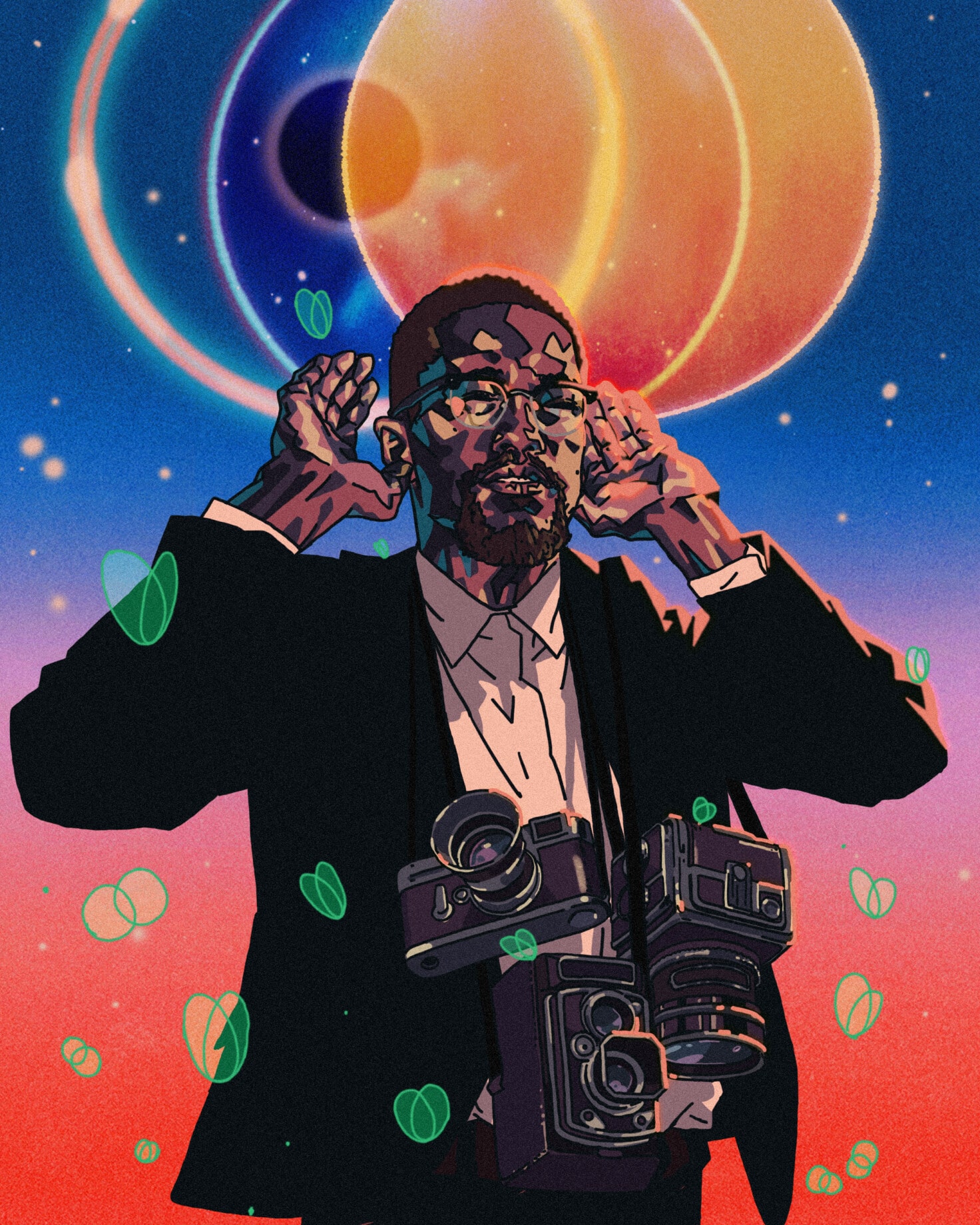

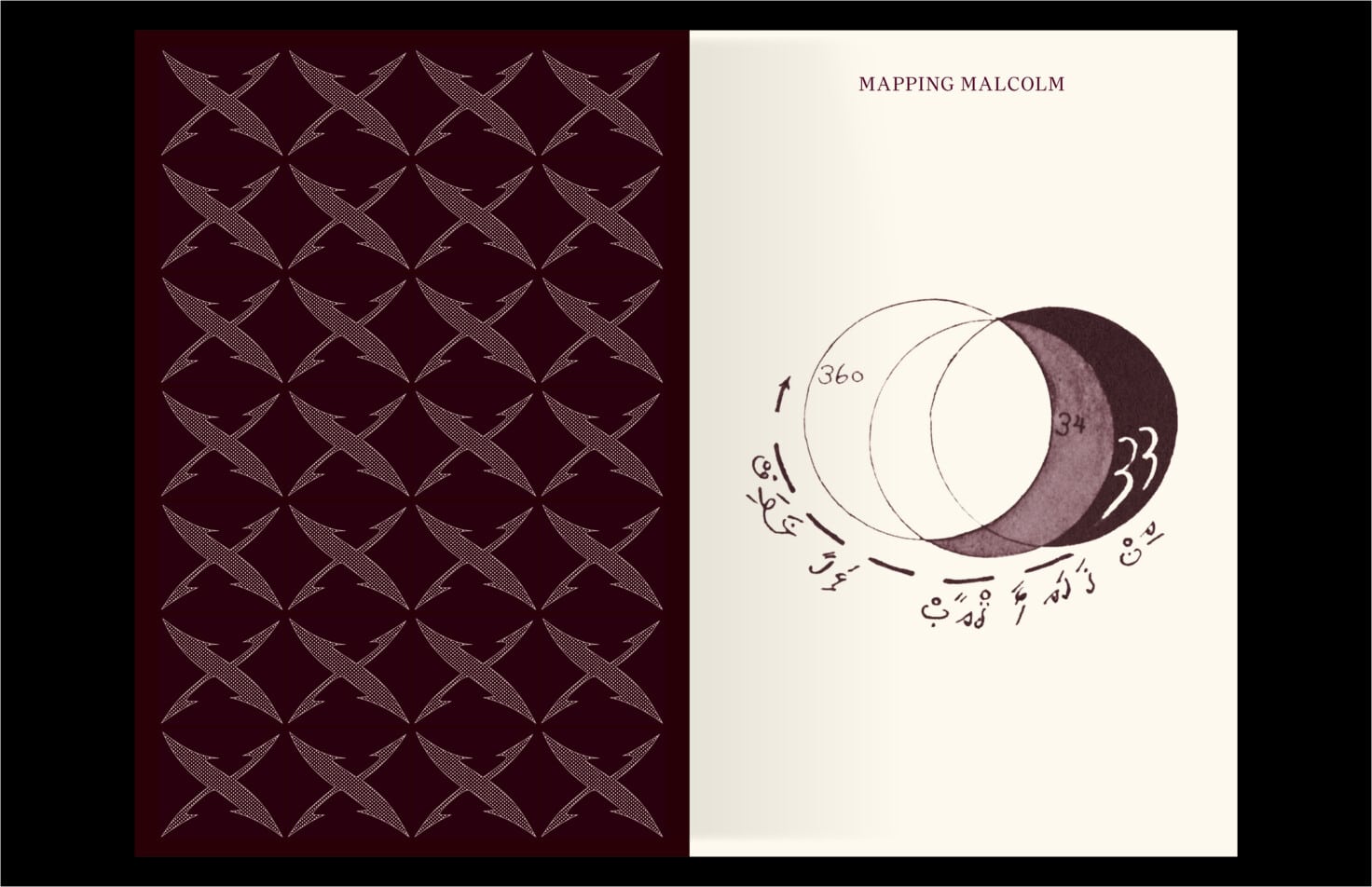

I often think about the beautifully intimate photographs that Malcolm X took of Maya Angelou and Shirley Graham Du Bois outside Shirley’s home in Accra, Ghana, in the spring of 1964.1 I think about how Malcolm must have considered which way the light was shining as he posed his kindred under the sun, capturing this moment on his 35-mm still film camera. Not only was Malcolm stirred by the political fervor and possibility of a newly freed Ghana, but through his camera he was able to capture the essence of this postcolonial project and the central importance that Black women necessarily assumed in the ethical reordering of society.

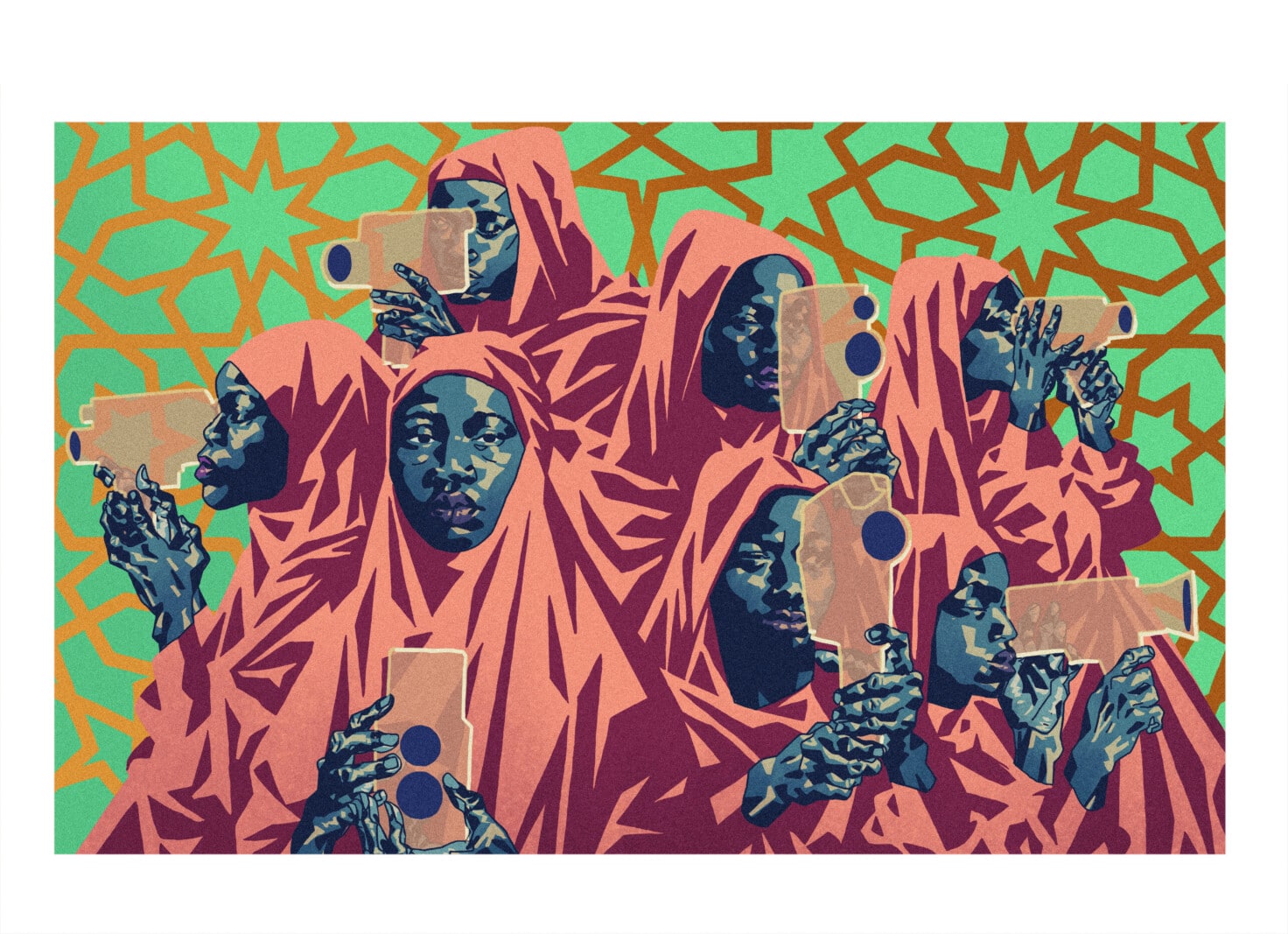

As I write these words and reflect on Malcolm’s encounter with the continent in all her righteous glory, I watch our world crumble as empire lights this earth ablaze. Many days, I feel as though I am drowning in my dread and yearning for a sort of honesty that feels incompatible with the lies and inhumanity that white supremacy demands from us. Sometimes seeing this truth for what it is feels like a burden too big to bear, and a new type of nihilism sets into my marrow. Other times, I feel this future we are being thrust into is asking that we gather our creative instruments and build our way forward with a vibrancy and artistic precision that extends beyond the dogma of traditional politicking. This is not to say that ideological clarity is not necessary, but revolution also needs the funk. Abstraction is our possibility, and prose our heartbeat. Indeed, our truth is our glory.