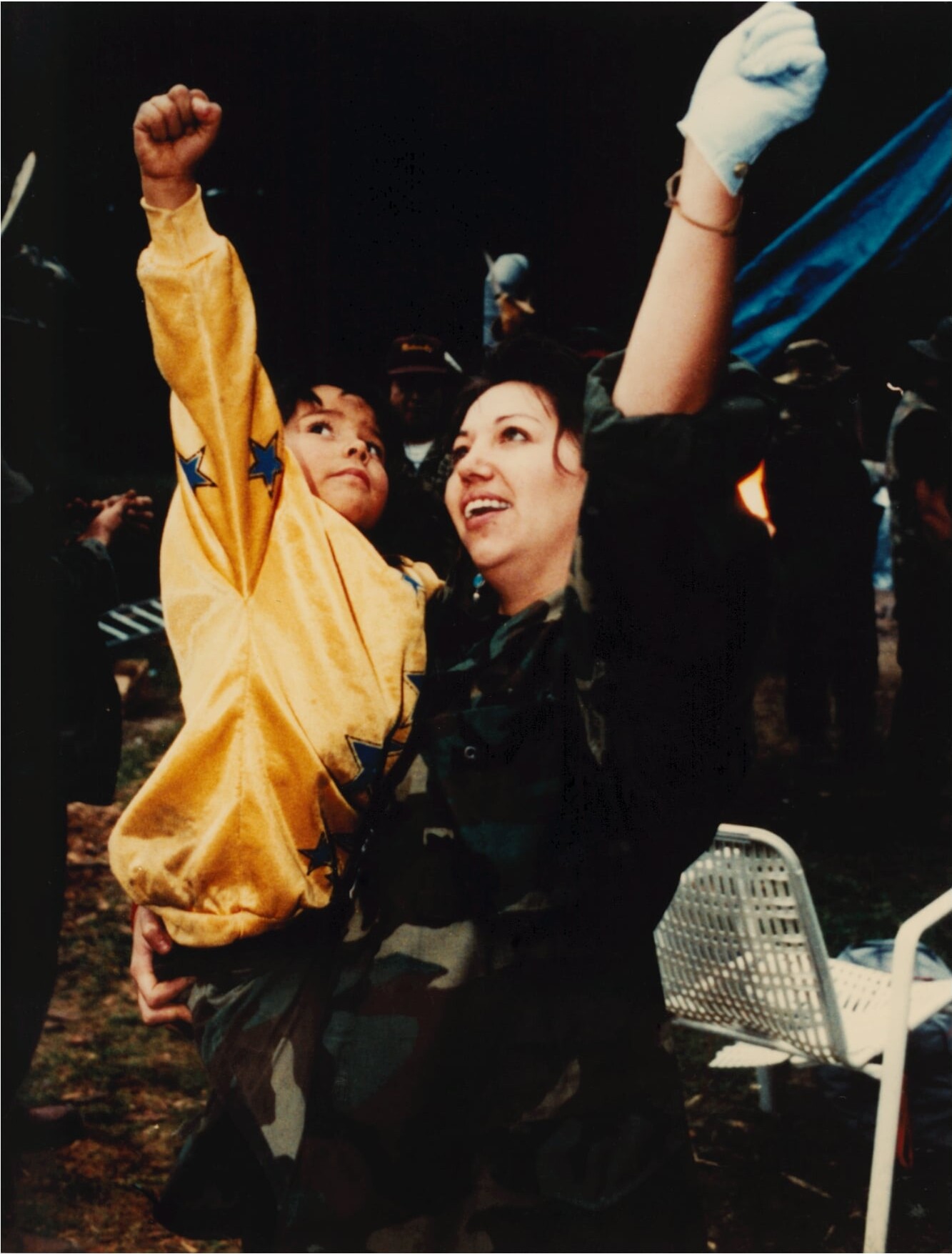

What unites these films is their relentless innovation. Each pushes the boundaries of the documentary form, embedding the voices and perspectives of marginalized communities into their very structure. They are not merely about their subjects; they are collaborations, disruptions, and reimaginings of how stories can be told. In Kanehsatake, Obomsawin’s presence becomes part of the narrative—a guiding voice that amplifies rather than overshadows. INAATE/SE/ dismantles linearity, creating a kaleidoscope of impressions that reflect the complexity of Indigenous experiences. As Long as the Rivers Run hints at the possibilities of a genre that listens more deeply, even as it struggles with the constraints of its perspective, especially considering the time in which it was made. And The Exiles, through its restoration and introduction into this nascent canon, forces us to confront how stories evolve over time, shaped by the contexts in which they are viewed.

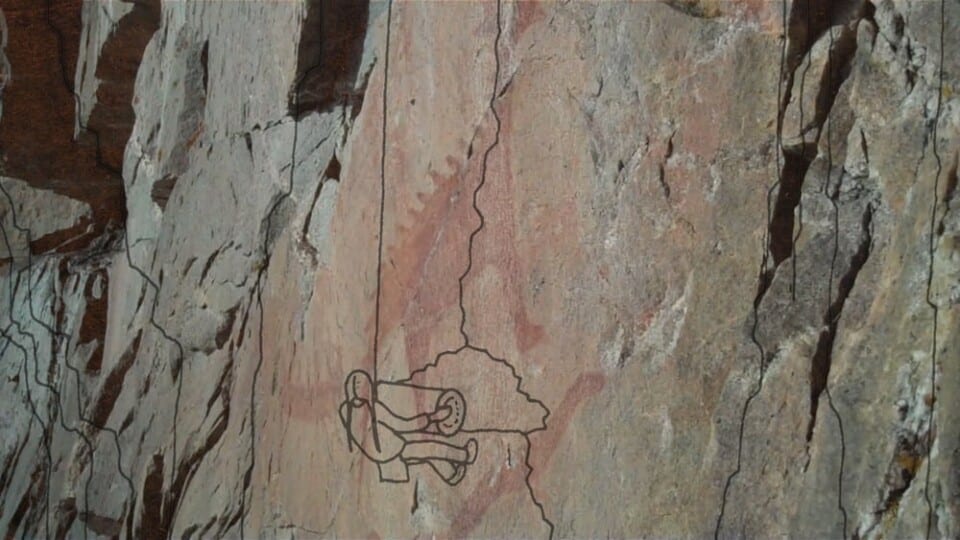

Water flows through these films—not as a mere symbol but as a force that connects and disrupts. The rivers of the Pacific Northwest in As Long as the Rivers Run are both of sustenance and struggle. In INAATE/SE/, the waterways of Anishinaabe lands ripple with echoes of prophecy. In Kanehsatake, the contested land is haunted by the rivers it has lost. Yet, in The Exiles, the absence of water in the urban sprawl reflects the slow painful process of relocation—a loss that stretches, dilates, and lingers in its emptiness. You feel the diasporic flow of the ebbs and tides of Natives leaving the reservation for the city, and returning when the money ran out or the promises of work dried up. Water becomes more than an element; it is an active participant in these narratives, carrying histories of survival and transformation.

The persistence of community and the refusal to be erased are also a vessel in these diegetic seas. These films do not flatten their subjects into tropes or artifacts. They expand, demand, and complicate—insisting on the depth and specificity of lives shaped by history, resistance, and creativity. They ask the viewer to reckon with the act of watching, to move beyond passive consumption and into a space of engagement. These are not stories told for closure; they are told to provoke, to challenge, to transform—not just the subjects, but also the audience and the form itself. To challenge this genre is not to discard its traditions, but all in service of moving it forward—to create something new that reflects the needs, passions, and visions of the communities they represent. This is an evolution, one that prioritizes the lived experience of those too often spoken for rather than listened to. These films insist that we hear, that we see, that we remember—remember the when and the then, the now and this moment, the context and struggle, and the simple joys we can’t comprehend anymore. Eventually we’ll find a way and a time to fit ourselves into some future’s past, another ripple among ripples folded into the flowing waters on a recurrent journey, like the rain from the clouds into the mountains into the rivers to the sea.