Back in 1997, with India celebrating 50 years of independence, artist Shaina Anand accompanied filmmaker Saeed Mirza on a journey travelling across the country, listening to and filming stories about the day-to-day lives of India’s citizens. Their journey culminated in Mirza’s A Tryst with the People of India (1997), an episodic documentary telecast on India’s public TV channel.

As an assistant director, Anand stayed up at night logging and cataloging all the day’s footage: noting names of speakers, tagging locations, summarizing what each person said at this significant moment in the national history. The inception of CAMP, the artist studio she cofounded with Sanjay Bhangar and Ashok Sukumaran in Mumbai in 2007, was still a decade away.

But the seeds had been planted.

CAMP’s manifesto from 2007 begins with a wish “to consider thresholds of ownership and authority as challenging sites for artistic practice.”1 Today, CAMP’s collaborative video and public art projects interrogate the assumed and easy relationship between author, viewer, and technology. Their work disrupts the power structure that exists between the person who holds the camera and the person who stands in front of it.

Through images, words, and videos, CAMP strives to create an ecosystem where the ideas of search and re-search are met with rigor and labor, and eschews a world where people turn to a state-controlled body (national archives), hegemonic power structures (academic archives), or tech conglomerates (internet search engines). In its archives, there are no search options for author and director.

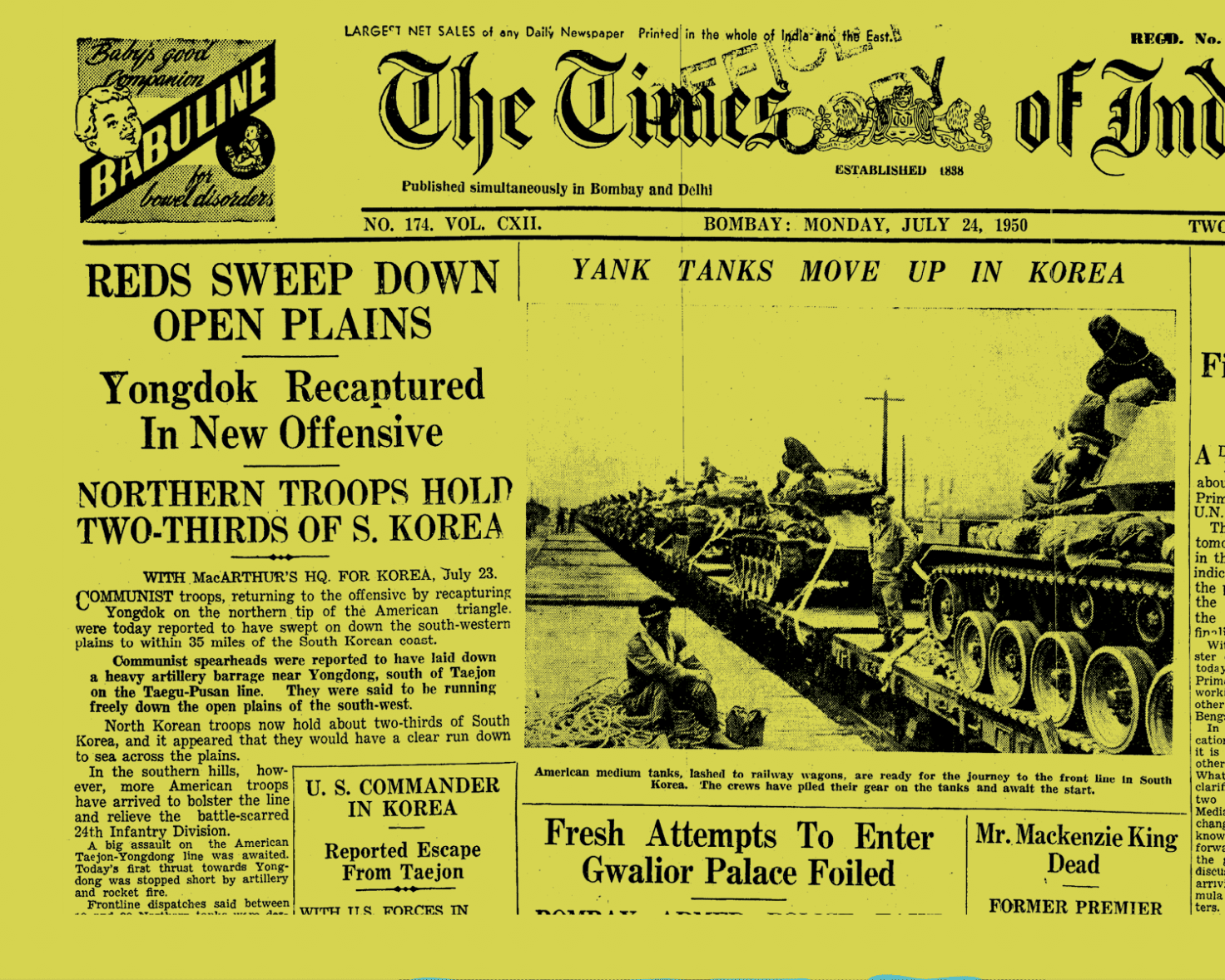

With its archives, CAMP creates knowledge storing and sharing structures that aim to be democratic and equitable. They create what Anand describes as “architectures of knowledge” that are generous and independent. CAMP’s autonomous and open-sourced existence offers a radical research alternative, especially within the context of ever-growing state censorship in India. “Any historian of Indian cinema must confront head-on the problem of the absent archive. Of all the films made in the Indian subcontinent between 1920 and 1950, less than 5% are preserved at the National Film Archives of India (NFAI),” writes film scholar Debashree Mukherjee.2