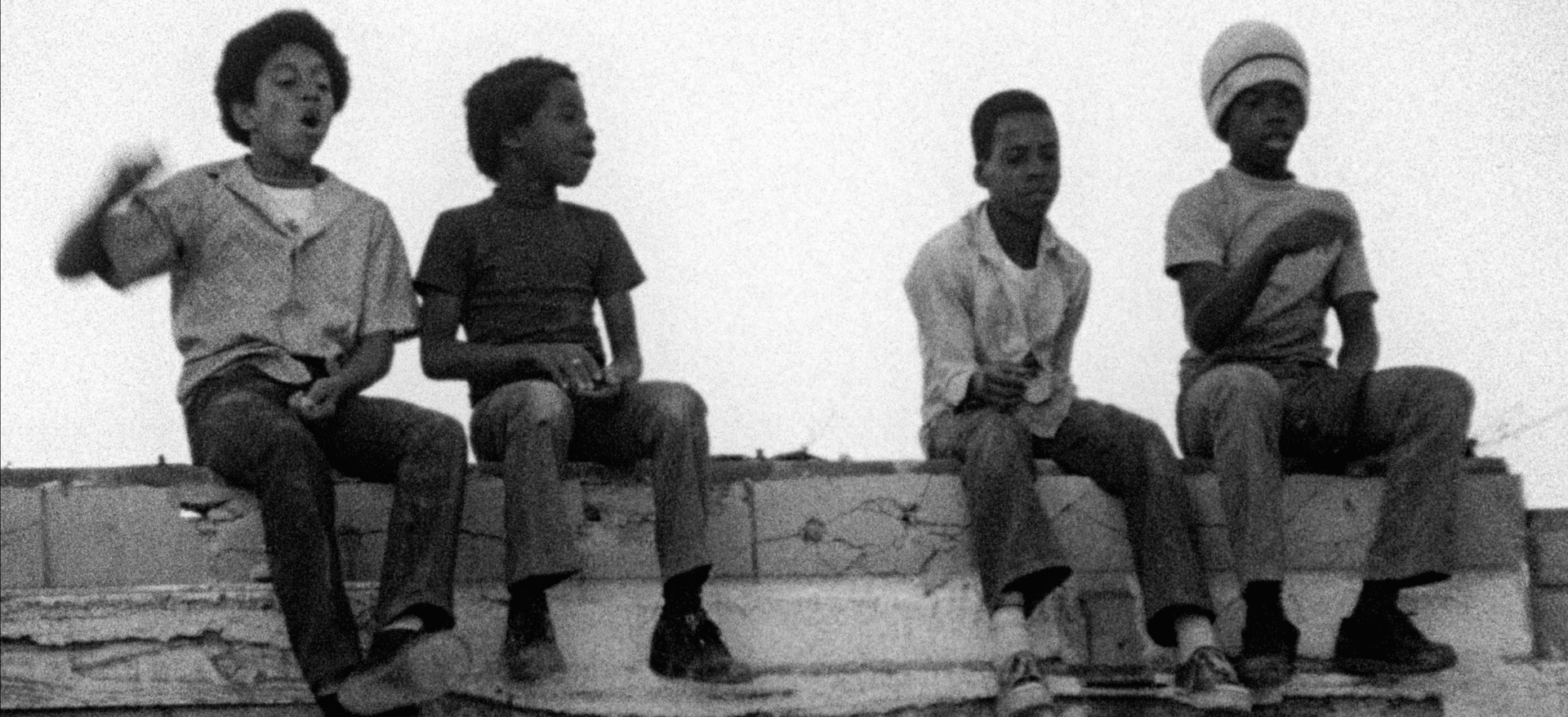

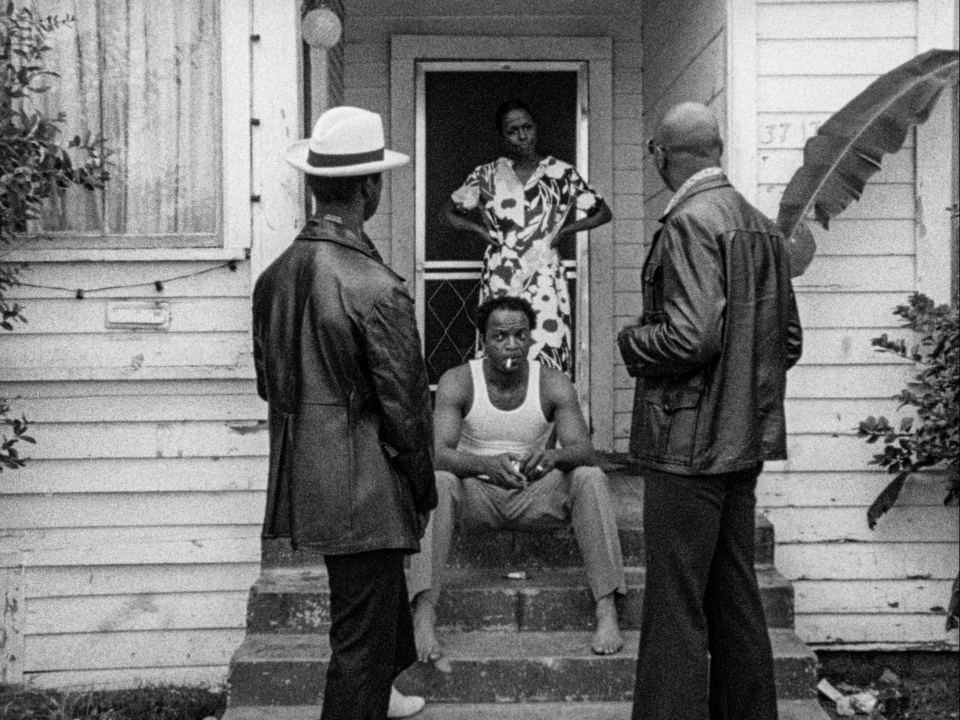

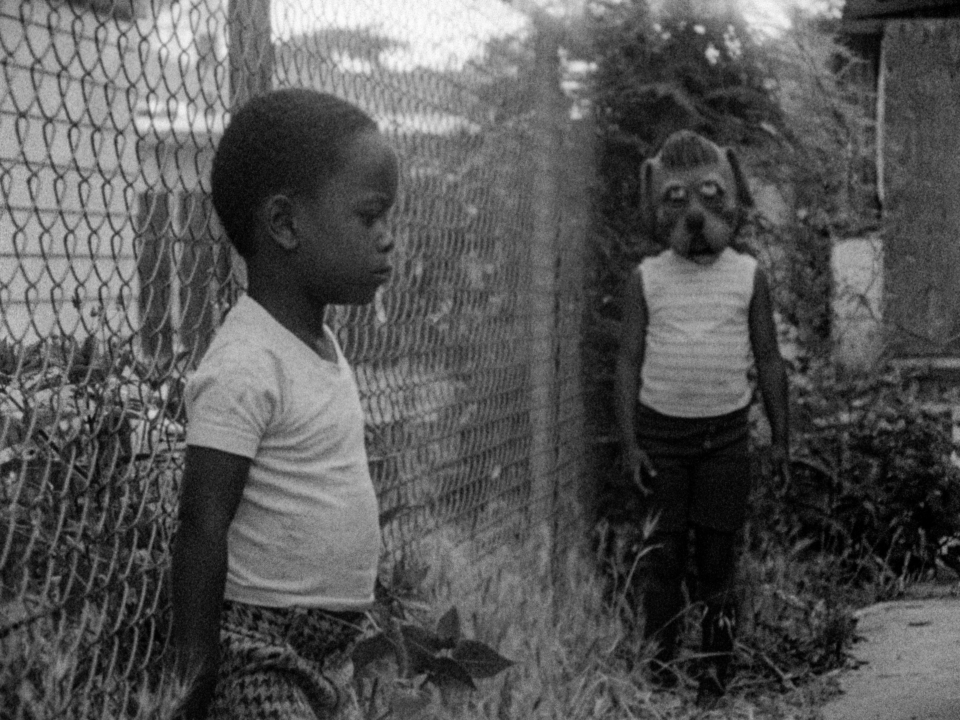

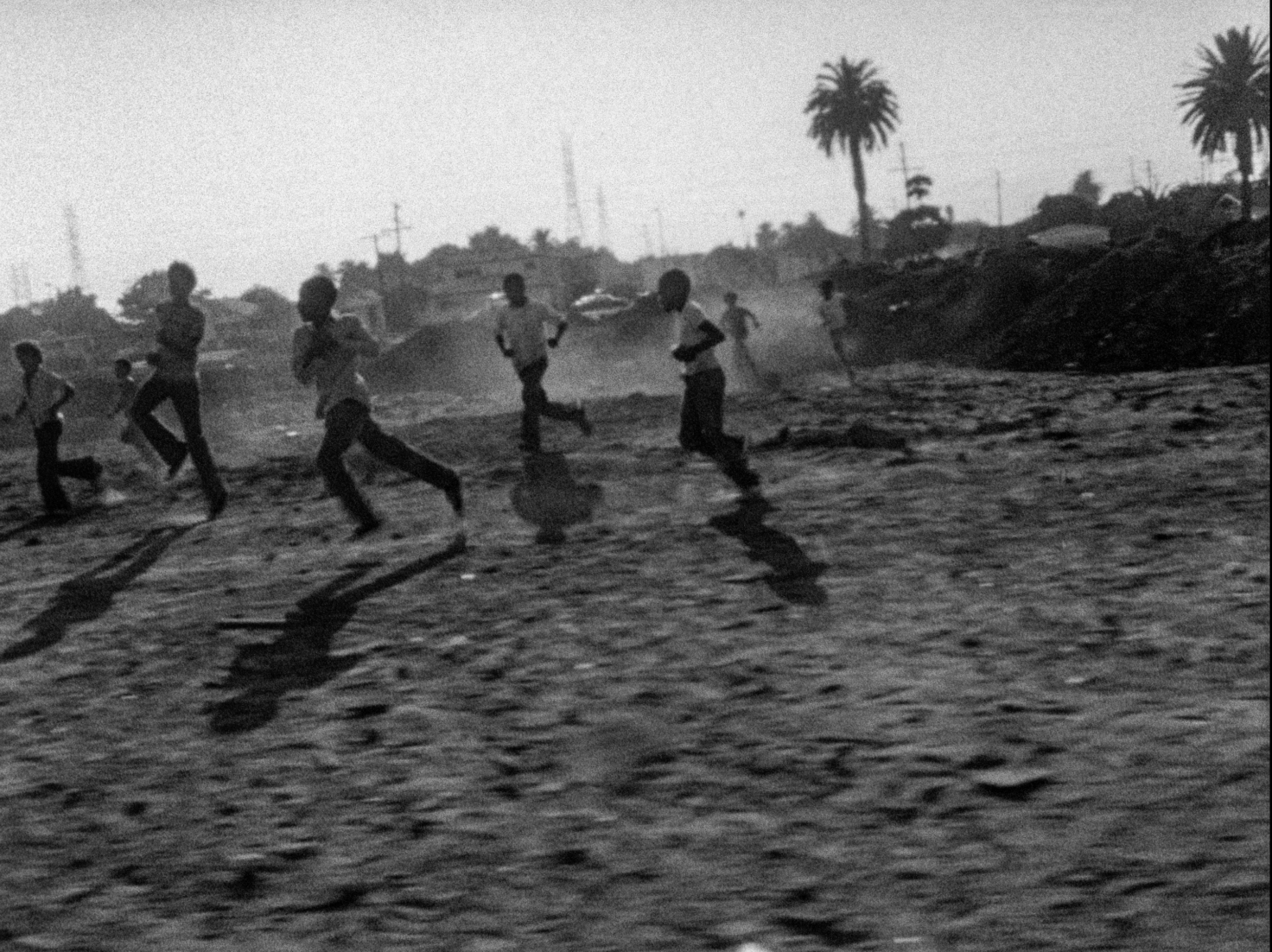

I was immediately struck by the film’s slow, meditative portrayal of Black life in South Central Los Angeles. Its pacing was alluring, perhaps mirroring my own internal rhythms, but also profoundly original—it was unlike anything I had experienced before in cinematic depictions of Black people. Having lived in Watts, to me the characters resonated; I vividly recognized my own family members in their faces. Beyond the powerful on-screen performances, the narrative behind the camera equally captivated me. Charles Burnett was community-minded in his approach to filmmaking, even involving children from the neighborhood in the production, viewing film as a tool for education and social change. I internalized this approach, making it my mandate: tell local, personal stories, with community, alongside friends.

The new 4K restoration of Killer of Sheep marks a significant cultural milestone. Most admirers of the film know the popular lore of how it went unseen for decades due to limited distribution and prohibitive music rights. To finally experience this American masterpiece in its full, pristine glory, digitally restored in 4K with its original sound mix, is to witness vital cinematic history in a new light. This current restoration allows new generations to appreciate Burnett’s singular vision with unprecedented clarity, making the film’s quiet power resonate more deeply than ever.

The film’s black-and-white cinematography, preserved from the original 16-mm negative, is a revelation in 4K. Every dusty street, worn face, and tender moment is rendered with a depth and clarity that intensifies the film’s melancholic beauty. This enhanced image ensures that the film’s “scratchy” look—a deliberate aesthetic choice by Burnett to convey realism—is presented as intended, rather than obscured by the flow of time and degradation. Beyond the visuals, the sound design, meticulously restored from the original 35-mm three-track master, is equally crucial. The iconic soundtrack, featuring Etta James, Dinah Washington, Paul Robeson, and including the reinstatement of previously missing tracks, tells its own story about Black life through its curation of sounds. This deliberately cuts against the viewer expectations prevalent during the Blaxploitation era. Where audiences might anticipate music akin to Willie Hutch’s “The Mack” or Curtis Mayfield’s “Super Fly,” they hear classic renditions of music from bygone eras. Killer of Sheep presents a longer, more dynamic history of Black music that stretches and defies genre, precisely because the lives it accompanies do the same.