Through language, image, and sound, the masters of cinema have become some of the greatest sculptors of time. Ezra Pound, the great twentieth-century American poet, spoke of an image as “that which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time.”1 Though this was primarily attributed to imagism and the poetics of language, cinema and the poetics of moving image emphasize this truth. To shape time in cinema is to use the visual image as material for which to build a story—just as the poet uses word and the musician uses sound, the cinematographer combines the corners of reality to shape an experience in twenty-four frames per second.

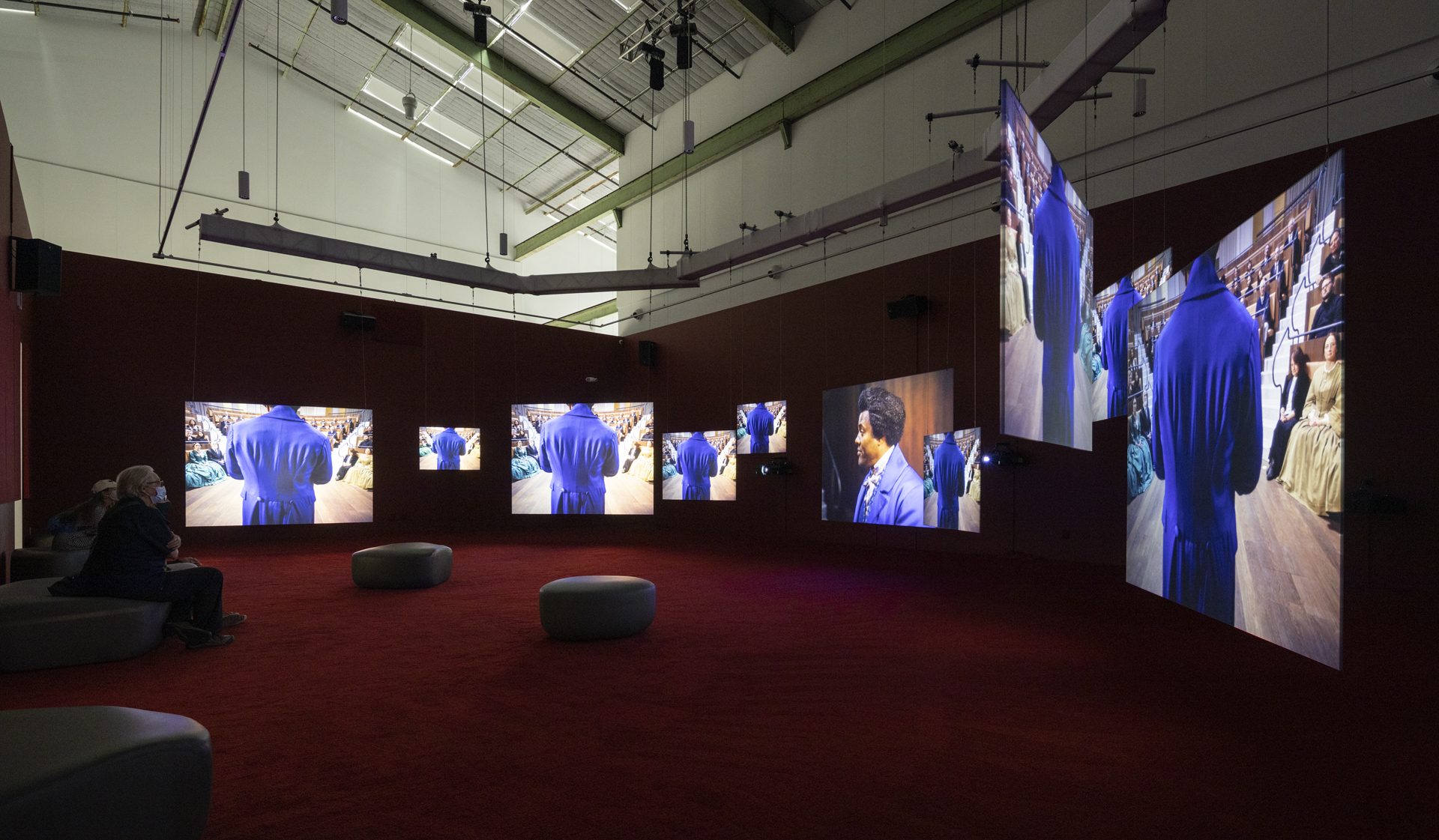

Isaac Julien’s Lessons of the Hour (2019), a spatial cinematic narrative presented across ten channels, draws a map that not only embodies “an instant of time” but—in language, image, and sound—shapes a temporal experience of the life of Frederick Douglass, who shaped time for descendants of the enslaved, in perpetuity, through his own mastery of language and poetics. It is in spatializing the moving image where the exercise of mapping time becomes a sensorial experience, further emphasizing the poetry in image and language. Think of the ways we experience cinema. In its most accessible formats, many of us watch on our personal devices, which facilitates the most practical viewing, but when we substitute access for experience, we lose the opportunity for immersive cinema. The most full-bodied experience most of the world has with film exists in the movie theater, but in a multichannel installation like Lessons of the Hour, image and sound can swallow us whole. When cinema expands beyond the traditional two-dimensional formats and into architecture, space becomes immaterial, and the ability to measure the passing of time dissolves in the hands of the filmmaker.