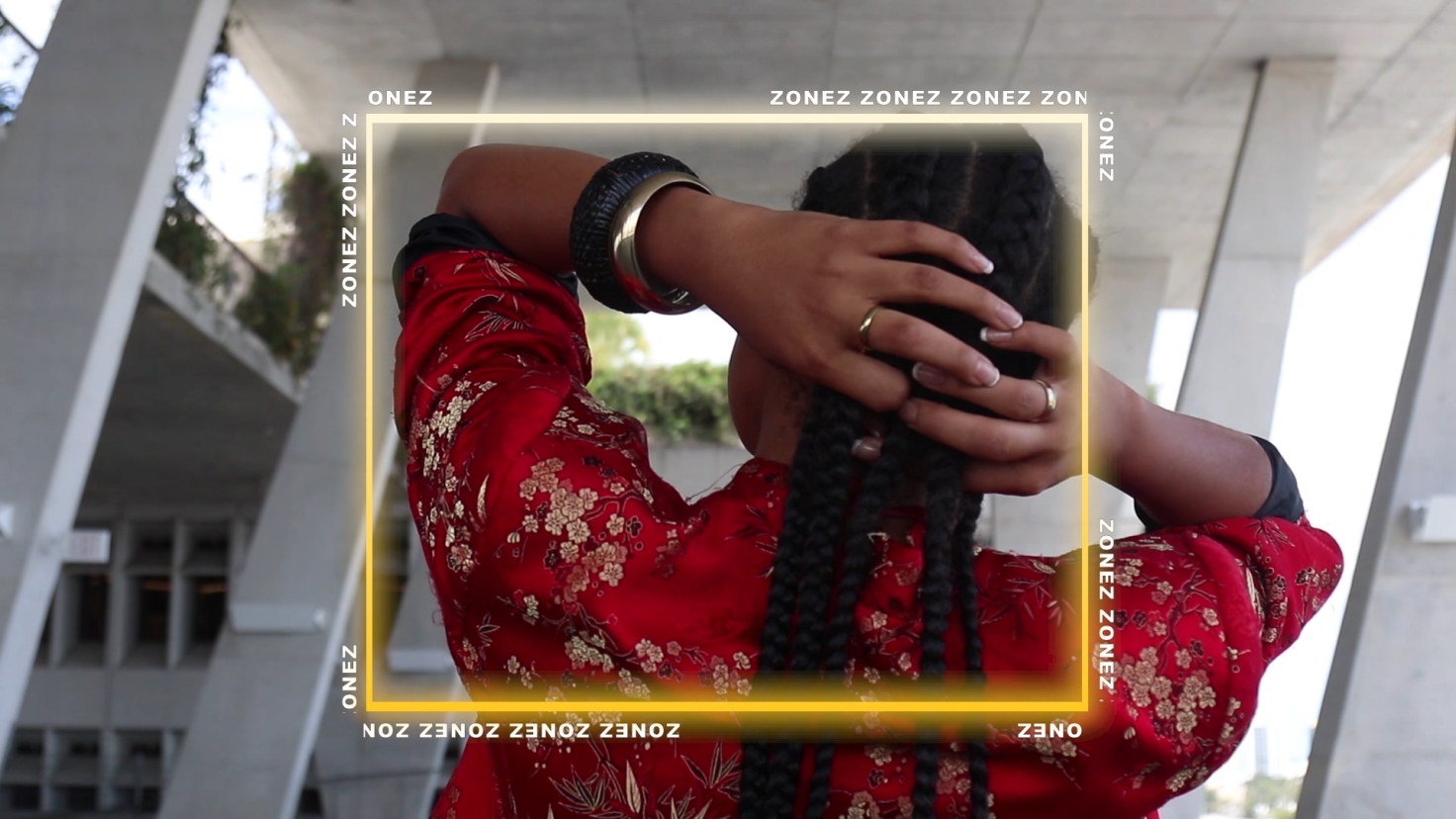

The term ZONEZ itself is a reflection of sorts: a word spelled to reflect the beginning Z as the ending Z, with ONE standing alone between it all—between progress that feels like change is near and history that signals this change is necessary. I likened myself to that ONE when conceptualizing this series living in the middle of a horrible election, great recession, and constant injustices against my bloodline. Up against the weight of this world, I lost all desire to be filmed for other people’s work anymore. I didn’t want to read lines of script and rehearse anything. When I recorded myself for ZONEZ, it was so I could be witnessed existing in the world, not simply surveilled by others.

Through these recordings that make up ZONEZ, my Black femme rawness is on display, showing that I exist in a world that tries to destroy my spirit, my identity. ZONEZ grants permission to view me gloriously out of the box, against any expectations that I should suffer and smile while carrying the weight of the world on my back as a Black femme. ZONEZ captures moments of surreality, inspired by my real-life awakenings. I have the autonomy to film myself living as freely as possible anywhere—I can eat flowers, or I can float free in the ocean, or I can dry my tears using the air from speakers, or I can dance within the glow of art that stirs my soul. I can film myself as I am.